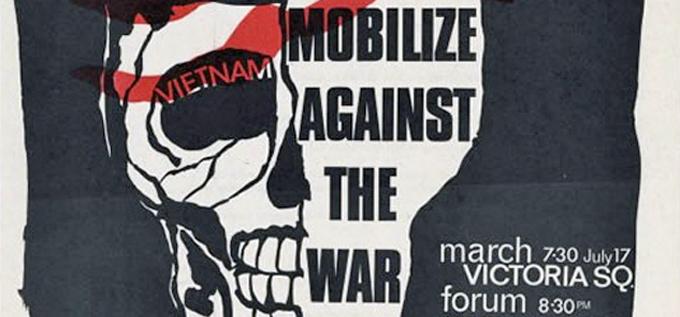

National mobilisation poster against the war in Vietnam, 1971 (Alexander Turnbull Library, MS-Papers-2511-5/1/25-9)

There was a vocal and well-organised anti-war movement in New Zealand. Worldwide protest against the war centred on the policies and actions of the United States government. Critics of the war accused the New Zealand government of simply doing what the US told it to, and called for a more independent, less submissive foreign policy position. Opponents of the war also questioned whether communism posed any real threat to New Zealand. While vocal, the domestic protest movement had negligible impact on New Zealand’s part in the war. Back home, however, it loomed large in the lives of service families. Many army wives stayed mum about their husband’s whereabouts, avoiding victimisation for their family’s association with an unpopular war. Servicemen’s children went to school with other ‘army brats’: their war was a shared reality and its spoils – Vietnamese toys and trinkets sent home by Dad – were coveted in the schoolyard. Wives cared for home and hearth, and spent their husband’s tour of duty waiting for word or a rare visit from an army padre or families officer.

Protest

Like their counterparts overseas, local protestors espoused moral objections to New Zealand’s participation in the Vietnam War, including opposition to the weapons and tactics being engaged, and their impact on innocent civilians. The extensive US bombing campaigns were a focal point for protesters, with anti-Vietnam war groups organising mobilisations against the war in major towns and cities. Thousands rallied against the war in notable public actions between 1967 and 1971. Anti-war slogans were rarely the only things hurled during rallies and demonstrations – eggs, paint and flour bombs were all used to reinforce the anti-war message. Anzac Day services, visiting Vietnamese and American diplomats, and the New Zealand Prime Minister were all targets of direct action. Firecrackers were thrown and 30 people arrested during a 1969 election meeting addressed by Keith Holyoake. Police clashed violently with anti-war demonstrators in Auckland during US Vice President Spiro Agnew’s visit in 1970.

Support for families

Relatives back home in New Zealand received little information or support from the army, while their loved ones were at war. Deployments generally took place without fanfare or interruption by protestors. Most army wives kissed their husband’s goodbye at home, and then relied on the kindness of friends and neighbours for help with domestic duties. For the first time in history families back home could monitor the war’s progress – and protests against it – on television. Media reports were a trusted source for information on the latest on troop movements. They were also how some women received news their husband was coming home. Some families were targeted in anti-war stunts. Phone calls to Waiouru army base were screened after wives were victims of prank calls – attributed to the Progressive Youth Movement – advising them of their husband’s demise in Vietnam.

Loss

For the families of 37 New Zealand servicemen and two civilian aid workers, the tragic news was not prank but reality. As in Korea in 1951, New Zealand’s first two fatal casualties in Vietnam happened during a move. On 14 September 1965, a Viet Cong mine exploded under the Land Rover driven by Sergeant Alistair Don and Bombardier Robert ‘Jock’ White, killing both men instantly. While they were buried at Terendak Cemetery, Malaysia, the majority of those New Zealanders killed in action or died of wounds in South Vietnam were returned home for burial. Some Vietnam veterans and families maintain that post-war deaths and sickness attributable to toxic exposure – namely the spraying of Agent Orange – should count in a tally of the war’s human cost. One such is Lynne Hawkins, widow of 1ALSG veteran Laurie Hawkins who died in 1996. In a poem dedicated to her husband’s memory, Lynne writes: “Unless you fell during battle New Zealand doesn't give a damn; But for a word on a gravestone; That says you fought in Vietnam; Not landmine, grenade nor bullet; Could permanently close your eyes; It was the silent stealth of ‘The Agent’; That attacked from out of the skies.” [1]

[1] Lynne Hawkins, 'Recognition - Poem', 2011, URL: http://www.vietnamwar.govt.nz/memory/recognition, accessed 13 April 2013

- At a price: manufacturing Agent Orange in NZ?Did Ivon Watkins Dow (IWD) manufacture Agent Orange in New Zealand during the Vietnam War?Read more...

- My childhood in the warI was born in 1968 when life was totally influenced by the terrible war.Read more...

- War correspondent - the story of Kate WebbKate Webb (1943-2007) was a New Zealand born war correspondent during the Vietnam War mistakenly Read more...

- New Zealand's day with LBJRead more...